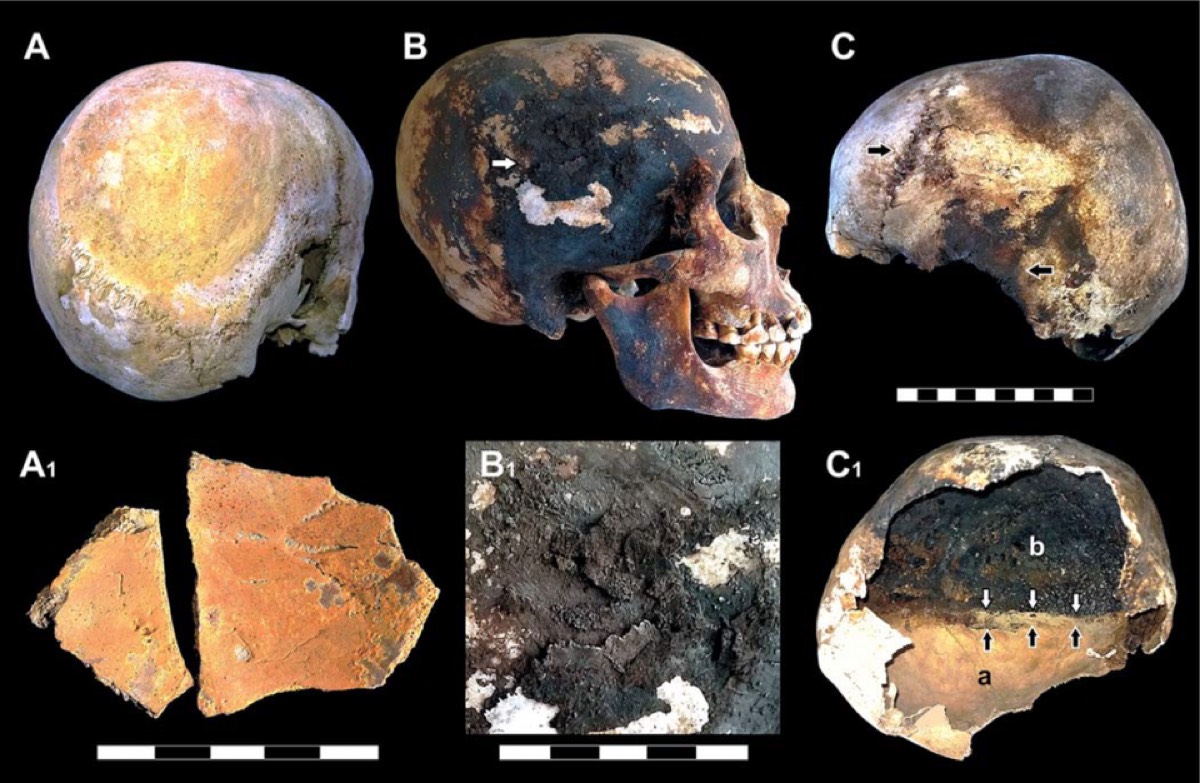

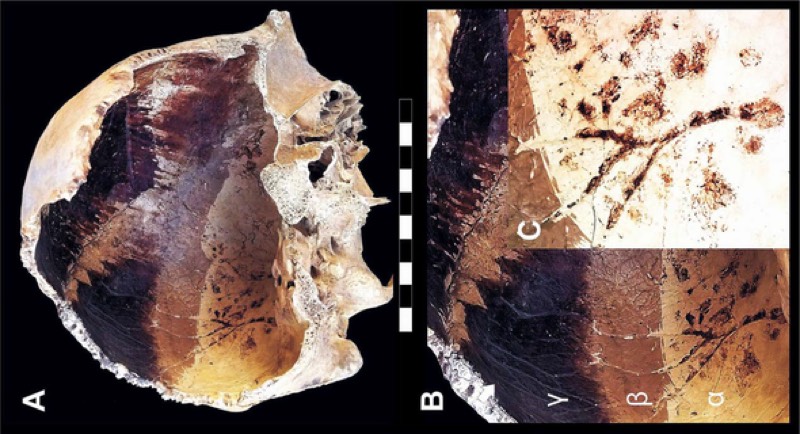

The catastrophic eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD wiped out several nearby towns and killed thousands of people. It has long been supposed that the vast majority died from asphyxiation, choking on the thick clouds of noxious gas and ash. But a recent paper by Italian archaeologists concludes that at least some of the Vesuvian victims died instantaneously from the intense heat of fast-moving lava flows, with temperatures high enough to boil brains and explode skulls.

As bioarchaeologist Kristina Killgrove notes over at Forbes, this new analysis, led by Pierpaolo Petrone of the University of Naples, builds on the Italian team's short 2001 paper in Nature. This is when they first broached their hypothesis, noting that the body postures of many victims unearthed in waterfront chambers in the town of Herculaneum, near the foot of Vesuvius, showed evidence of thermal shock. There were telltale flexed body parts, like curled toes and charred bones, indicating sudden death from a blast of extreme heat.

It is estimated that the eruption of Vesuvius released 100,000 times the thermal energy of the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, ejecting many tons of molten rock, pumice, and hot ash over the course of two days. In the first phase, immediately after the eruption, a long column of ash and pumice blanketed the surrounding towns, most notably Pompeii and Herculaneum. By late night or early morning, pyroclastic flows (fast-moving hot ash, lava fragments, and gases) swept through and obliterated what remained, leaving the bodies of the victims frozen in seeming suspended action.

Loading comments...

Loading comments...